A few months ago, I wrote a lonely blog about early detection and rapid response, invasives and this plant New Invasive; Early Detection; Rapid Response. I received no response, limited detection and no comments, but fortunately friends of the park are on patrol.

"Anacostia Watershed Society and MNCPPC, Prince Georges County,

will host 50 members of The International Finance Corporation, a branch

of the World Bank, at Little Paint Branch Park in Beltsville June 21, 2007.

It will be an educational example of early detection/rapid response

for a continent. It is requested that MA-EPPC, MISC and NCR EPMT

GPS the site for Oplismenus inflorescence, Wavy-leaf basket grass

which is highly invasive and has just hit North America, before the

volunteers remove it from 9am-4pm.

This grass is very invasive in areas adjacent to wetlands and in edge wetlands

We can start with the 3 acres of infestation in the 150 acres of Little Paint

Branch Park in Beltsville and then continues GPS ing up and down stream

in the watershed.

We meet at the Beltsville Community Center parking lot in Little Paint Branch Park and can continue even with a little rain or heat. There are full indoor toilet facilities and a large seating area for lunch.

We take U.S. 1 north from the beltway. Go about 1 mile, passing the National Agricultural Research Center, and turn left at the light on Montgomery Rd. Go 3 blocks and turn left on Sellman Road. Go about 5 blocks and turn right into Little Paint Branch Park at the bottom of the hill. Cheers. Marc Imlay, PhDConservation biologist, Anacostia Watershed Society(301-699-6204, 301-283-0808 301-442-5657 cell)Board member of the Mid-Atlantic Exotic Pest Plant Council,Hui o Laka at Kokee State Park, HawaiiVice president of the Maryland Native Plant Society,Chair of the Biodiversity and Habitat Stewardship Committeefor the Maryland Chapter of the Sierra Club"

Program manager, policy analyst: invasive species, ecosystems, agricultural, horticultural and environmental research and bioeconomic policy consultant and advocate.

Tuesday, May 29, 2007

Friday, May 25, 2007

More Invasive Species Musings

Today, I met a customer who a number of years ago, trusting our nursery to steer her towards quality plants, purchased a novel introduction that we were marketing. Today she is waging war and justifiably upset that she must spend time and resources to reclaim her garden from Polygonum cuspidatum, which was sold to her under the name Fallopia japonica. [picture from USDA]

Today, I met a customer who a number of years ago, trusting our nursery to steer her towards quality plants, purchased a novel introduction that we were marketing. Today she is waging war and justifiably upset that she must spend time and resources to reclaim her garden from Polygonum cuspidatum, which was sold to her under the name Fallopia japonica. [picture from USDA]This is the story of the traditional market driven need for the latest and the newest. Each year we look for the latest, newest car design; the newest refrigerator in the latest shade of white; the most recent designed shoe from Milan, and the novel flower introduction from exotica. New sells, and new drive our market economy; selling the newest potentially invasive returns to haunt.

On the issue of invasive species, as with many ideas in the world, I find myself a radical moderate. When all the stakeholders think that I hold incorrect views, I suspect that I have found the middle of the controversy. And from the middle, I seek to weigh the information from all sides and to establish a working compromise with as many stakeholders as I can find. There are those who would say that the issue of invasive species is simple and straightforward, and that my attempt at moderation is counterproductive for all non natives must be removed and no new introductions be allowed to settle. And there are those who say, let the market decide, stay out of the way.

The small delightful reptile sold to a young person for a few dollars grows up to be a 200 pound Burmese python. It seems, after having met the snake close up and personal, that sales without limit are problematic at best. And one can make the case based upon most people's fear of snakes that sales should be severely restricted. This restriction is much harder to do with a flower which grows under almost any condition and blooms from late spring to frost almost anywhere in the US - Lythrum. And yet the snake and the flower have some similarities below the surface.

The small delightful reptile sold to a young person for a few dollars grows up to be a 200 pound Burmese python. It seems, after having met the snake close up and personal, that sales without limit are problematic at best. And one can make the case based upon most people's fear of snakes that sales should be severely restricted. This restriction is much harder to do with a flower which grows under almost any condition and blooms from late spring to frost almost anywhere in the US - Lythrum. And yet the snake and the flower have some similarities below the surface.As I have written before, the wicked inconvenience of invasive species rests upon the underlying aggregation of complexities that ensnare those who consider on the surface issue. Invasive species issues are four dimensional, but much of the discussion is only one of place; time is not included. Many who sincerely try to rescue and restore our last remaining natural areas are trapped by focusing on the small/fast interactions of a self sustaining ecosystem such is found when Japanese knotweed terrorizes a garden or natural area. The very nature of the large/slow interactions which, when one attempts to forecast, are beyond our human temporal horizon and therefore at best are present fact supported conjectures leads quite often to argument without the possibility of end.

Because invasive species are a wicked problem, there is no end, and the inconvenience that results from defining the problem from one’s end goal leads to stakeholders talking past each other rather than with each other. Those who would plant only natives in urban settings are perforce looking to the past to determine the palette of natives. They are assuming that in the changing dynamics of a disturbed area, the natives of the past will thrive. They are attempting to return us to a “pristine” setting. This description itself is simplistic, for at a more complex level, the native only stakeholder is attempting to garden a self-sustaining ecosystem.

Another feature of a wicked problem is that there is usually a coequal, co-evolving wicked problem that increases the complexities of understanding. In the case of invasive species, the coequal problem is climate change. What is native today will be moving up and north as the temperatures rise, and new natives will be making inroads in our natural areas. We must always beware of native to when and where.

Invasive species, however, call for action. I use the poor analogy of weeds in an ornamental garden which must be continuously addressed or the garden (system) will certainly crash. As we garden we learn which plants “work” together, and which are to be avoided. It seems to me that the same outlook applies to natural areas. Those who traffic in living organisms have a responsibility to supply as much information about a species as possible to the end user including possible negative effects on the local environment.

Should we sell invasive species? For the past decade, we have tried to find a middle path. We long ago discontinued sales of Lythrum unilaterally, but we still sell English ivy. We post warning signs on the ivy, barberry, miscanthus, and euonymus, and have recently stopped selling all types of “Bradford” pears. We feature “Baysafe” plants, a term we trade-marked (native to the mid Atlantic) and try to educate the consumer to the right choice. To say there is no problem is manifestly wrong to me; to dictate based on changing science and understanding to the consumer is counter intuitive to a member of the merchant class. How we define a beautiful landscape must begin to include a sense of beauty beheld in a working ecosystem.

Monday, May 21, 2007

Invasive Species and BARC - Beltsville Agricultural Research Center

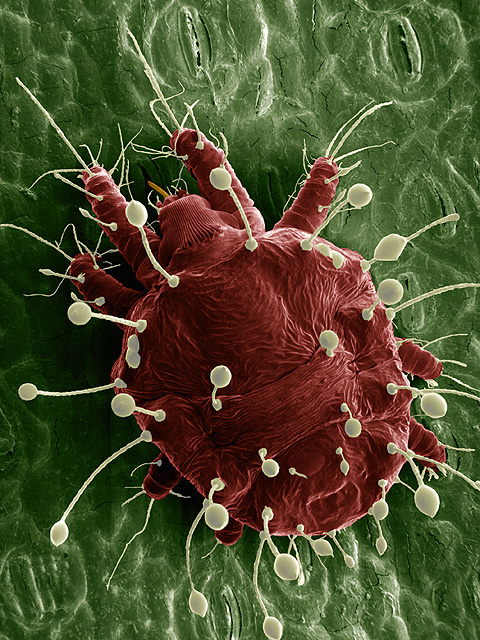

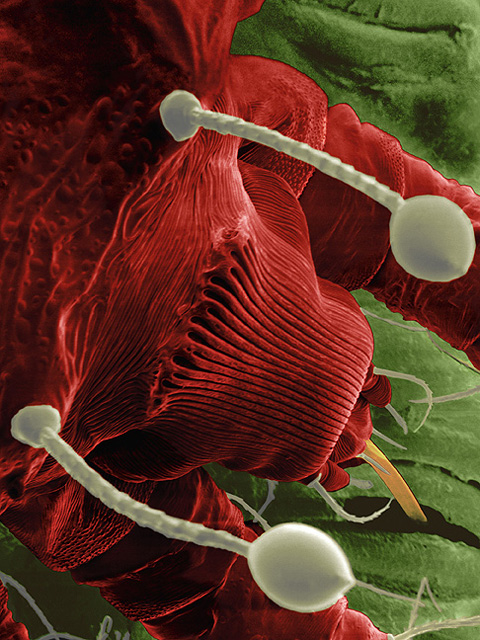

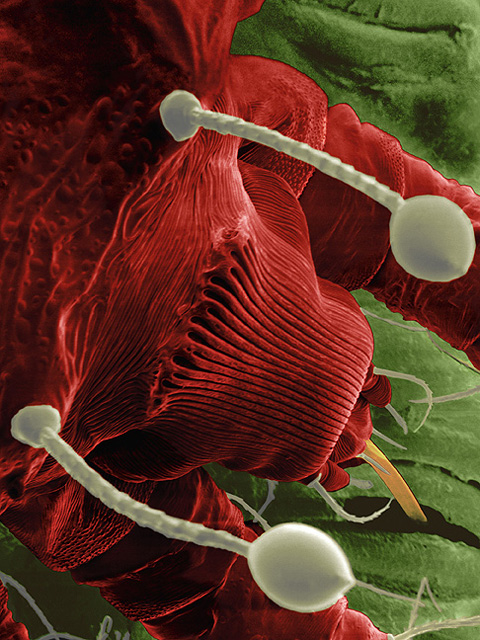

Pictures copied from USDA: A Tiny Menace Island-Hops the Caribbean

Pictures copied from USDA: A Tiny Menace Island-Hops the CaribbeanYet another invasive species is preparing to make landfall in the United States. The red palm mite, Raoiella indica, which can move through wind storms from island to island is also being intercepted on the straw hats of American tourists returning from holidays in the Caribbean. In a wonderful confluence of topics, it is the Beltsville Agricultural Research Center that is a leading contributor to our scientific understanding of this pest.

Many times, gardeners shudder at the sound of proposed restrictions on beloved plants and vilify those researching the effects of invasive species. Yet in almost the same breathe, they come to expect the United States Department of Agriculture to hurry up and defend their gardens against invasive insects and diseases. This year, the current budget proposal for USDA BARC recommends a 5.5 million dollar cut More at the end of this posting on BARC proposed budget cuts.

Invasive species issues are currently defined from the point of view of “natural” area preservation, and not from the ornamental horticulturists’ point of view. It is almost a given certainty that naturalists and gardeners will both endeavor to stop the red palm mite and would support each other in “radical” calls to ban straw hats from vacationers returning to American ports.

“For one, it has spread to other exotic and ornamental palms,” says Ochoa. “And on Dominica, it’s attacking banana plants. In Trinidad, it was observed on Heliconia. Overall, we’re talking about a potentially devastating economic impact. [A Tiny Menace Island-Hops the Caribbean]

Interestingly this invasive species is a challenge to definitions, because if it comes on the winds of a hurricane, then we do not have the direct hand of man involved. Of course if you say that global climate change is because of man then indirectly the hurricanes are the fault of us and we do not violate the federal definition.

So back to BARC and its finding challenges. If we are going to address and understand our brave new world, we will need the basic science of agriculture to help us find our way. We need more science not less.

So back to BARC and its finding challenges. If we are going to address and understand our brave new world, we will need the basic science of agriculture to help us find our way. We need more science not less.

Many times, gardeners shudder at the sound of proposed restrictions on beloved plants and vilify those researching the effects of invasive species. Yet in almost the same breathe, they come to expect the United States Department of Agriculture to hurry up and defend their gardens against invasive insects and diseases. This year, the current budget proposal for USDA BARC recommends a 5.5 million dollar cut More at the end of this posting on BARC proposed budget cuts.

Invasive species issues are currently defined from the point of view of “natural” area preservation, and not from the ornamental horticulturists’ point of view. It is almost a given certainty that naturalists and gardeners will both endeavor to stop the red palm mite and would support each other in “radical” calls to ban straw hats from vacationers returning to American ports.

“For one, it has spread to other exotic and ornamental palms,” says Ochoa. “And on Dominica, it’s attacking banana plants. In Trinidad, it was observed on Heliconia. Overall, we’re talking about a potentially devastating economic impact. [A Tiny Menace Island-Hops the Caribbean]

Interestingly this invasive species is a challenge to definitions, because if it comes on the winds of a hurricane, then we do not have the direct hand of man involved. Of course if you say that global climate change is because of man then indirectly the hurricanes are the fault of us and we do not violate the federal definition.

So back to BARC and its finding challenges. If we are going to address and understand our brave new world, we will need the basic science of agriculture to help us find our way. We need more science not less.

So back to BARC and its finding challenges. If we are going to address and understand our brave new world, we will need the basic science of agriculture to help us find our way. We need more science not less.Here is a list of current programs which will take hits this year of congress can not be persuaded to add the money back.

Dairy genetics: continue long-term genetic improvement in dairy cattle, increasing milk yield per cow and feed efficiency (milk produced per pound of feed) over many years.

Barley health food benefits: study barley soluble fiber compounds to lower blood cholesterol and improve insulin and blood sugar control.

Biomineral soil amendments for control of nematodes: research using industrial byproducts as environmentally benign soil additives to control crop damaging nematodes.

Foundry Sand byproducts utilization: develop guidelines for agricultural uses of waste sands from the metal-casting industry; waste sands now are dumped in landfills.

Poultry disease (avian coccidiosis): understanding the genetics of the parasite-host relationship in Coccidiosis, a parasitic disease that costs the poultry industry $2-3 billion annually.

Biomedical materials in plants: using plants to grow vaccines and other pharmaceuticals for both animals and humans, at times referred to as “pharming”.

National Germplasm Resources Program: maintain and service national plant germplasm resources collected over many decades by plant exploration around the world—a vital, irreplaceable scientific resource.

Bovine genetics: research functional bovine genomics to identify specific genes for such traits as easier calving, higher milk production, and resistance to mastitis.

Minor-use pesticides (IR-4): study pest control for such crops as fruits and vegetables, which major corporations for economic reasons tend to overlook for the bigger markets of corn, wheat, and soybeans, and cotton—the “big four” of American crops.

National Nutrition Monitoring System: carry out national surveys of food consumption by individuals and maintain the National Nutrient Database—done in collaboration with HHS, these activities support the school lunch program, WIC, Food Stamps, senior nutrition programs, food labeling, dietetic practices, and others.

Coffee and Cocoa: research to develop environmentally friendly ways to control pests and diseases, and support U.S. chocolate candy production—the single largest U.S. user of fluid milk, sugar, peanuts, and almonds.

Johne’s disease: research this contagious bacterial disease of ruminants, affecting most often dairy cattle—milk producers lose over $54 million annually to this disease.

Food safety—listeria, E.coli, and salmonella: these food-borne illness annually costs $3 billion in health-care costs, and annually costs the economy up to $40 billion in lost productivity.

Weed management research: this research, in collaboration with the Rodale Institute and Pennsylvania State University, studies systems for controlling weeds in organic production systems.

This is your time to get political and call your state Senators and Congressmen; tell them to stop cutting basic science which supports our understanding and our life styles. Who thinks in today’s news market place that we need less E. coli research?

Remind me to write about the National Agricultural Library and its budget problems.

Friday, May 11, 2007

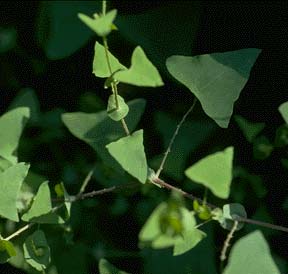

Invasive plant "hides" behind new name

News flash: "....The dismantling of Polygonum sensu lato has been gradually gaining favor since the earlier papers of Haraldson (1978) and Ronse Decraene & Akeroyd (1988). For example, it is adopted in the Med-Checklist, the Flora of Japan (2006), in Families and Genera of Vascular Plants (Brandbyge in Kubitzki, 1993), and will be adopted in the upcoming Flora of Australia (fide Wilson 1990). In GRIN we chose to retain Polygonum in its original sense until the Flora of North America treatment appeared (in vol. 5. 2005), since all North American floras had ignored this split as well. Once FNA endorsed this view our GRIN data were converted to agree with them...." [John H. Wiersema, Ph.D.Curator of GRIN Taxonomy (www.ars-grin.gov/cgi-bin/npgs/html/index.pl)United States Department of Agriculture/Agricultural Research Service Systematic Botany & Mycology Laboratory Bldg. 011A, Beltsville Agricultural Research Center (BARC-West)Beltsville, MD 20705-2350 U.S.A.Tel: 1-301-504-9181 Fax: 1-301-504-5810 Email: jwiersema@ars-grin.gov]; [picture of mile-a-minute weed courtesy of Jil M. Swearingen, U.S. National Park Service, Washington, DC]

Mile-a-minute weed had been changed to Persicaria perfoliata previously recognized as a synonym for Polygonum perfoliatum, which has been the accepted name for a number of years now. Just when you thought you knew 'em, they get an also know as.

Garden Alternatives to Invasive Species in the Mid Atlantic region

For many gardeners, the read word “Invasive” spreads terror and discord and creates great waves of anxiety and negative waves of resentment. Currently, invasive plants defined to be non-native, exotic, aliens which reproduce furiously replacing native species and complex self-sustaining eco-systems with, in some cases, biological deserts or mono-cultures.

The very reasons, which sustain invasive plants, also find their way into gardens and horticulture. Cheap to propagate, easy to grow, indestructible under all conditions, and easy for the consumer to find have the makings for a champion garden trade species. And the wider the conditions a plant may grow in, the wider the trade in the plant, and, so, the wider the distribution to places and eco-systems which can not tolerate the incursion of the new species.

One way to think of invasive species is to think of all the weeds, we do not want in our gardens. The worse ones are those that creep in from our neighbors untended mini-estates. Think running bamboo, and understand the feelings of those who are charged with protecting natural areas. They are gardening with a native only concept, and we are gardening with the anything goes model. This situation makes for uneasy neighbors, and opportunities for stress and misunderstandings.

Not all invasive species were introduced by gardeners or garden centers. Many simply hitched a ride on the bottom of a boot or in the cargo hold of a transport ship; even in the crates of packing materials we use to ship our consumer goods have held invasive surprises. But some, like kudzu were originally introduced by the horticulture industry (1876), even though it took federal help to find its place in our southern landscapes. Callery pear hybrids abound in the mid Atlantic region as a highly recognizable invasive species, and are still recommended by local government agencies (Prince George’s County Tree) as a street tree choice, even though, the tree is almost always a bad long term landscaping solution.

Who are some of the bad actors and what can we replace them with? Lythrum, purple loosestrife, a perennial favorite which can be replaced with Liatris spicata, gay feather or blazing star, is an excellent native alternative for Lythrum. Liatris is easily grown in average, medium wet, well-drained soils in full sun. Though preferring moist, fertile soils and tolerant of poor soils, drought, summer heat and humidity, Liatris can be intolerant of wet soils in winter. The 2 foot tall clump forming perennial has long spikes of rounded, fluffy, deep purple flower heads, appearing atop rigid, erect, leafy flower stalks. [picture of Liatris courtsy of www.botany.wisc.edu/]

Who are some of the bad actors and what can we replace them with? Lythrum, purple loosestrife, a perennial favorite which can be replaced with Liatris spicata, gay feather or blazing star, is an excellent native alternative for Lythrum. Liatris is easily grown in average, medium wet, well-drained soils in full sun. Though preferring moist, fertile soils and tolerant of poor soils, drought, summer heat and humidity, Liatris can be intolerant of wet soils in winter. The 2 foot tall clump forming perennial has long spikes of rounded, fluffy, deep purple flower heads, appearing atop rigid, erect, leafy flower stalks. [picture of Liatris courtsy of www.botany.wisc.edu/]

If you are seeking a long summer bloomer to match the floral display of Lythrum, try hybrid hibiscus such as Lord Baltimore. Huge flowers, reliably perennial and fast growing, this plant will fill the summer and fall garden with knock your socks off beauty until frost. Liking wet soils, I have seen them tolerate some fairly dry conditions, and since they grow so fast, they can out-compete many pests, such as another invasive species, the Japanese beetle.

Another bad actor is English ivy. Drive through rock Creek Park in Washington or the grounds of my house, and probably your house, too, and the evergreen vine which is pulling off all the lateral branches of the shade trees is Hedera helix. Just a note, if it is not native and is just greening up now in the spring, and is climbing your trees, it is our native poison ivy.

It is tough to beat English ivy for an all purpose practical, indestructible, inexpensive, easy-to-grow, ground cover. You do not need to weed it, feed it, water it, mow it, trim it or think about it until it pulls down a major shade tree or your gutter system to your house. [picture of wisteria courtesy of Larry Hurley]

easy-to-grow, ground cover. You do not need to weed it, feed it, water it, mow it, trim it or think about it until it pulls down a major shade tree or your gutter system to your house. [picture of wisteria courtesy of Larry Hurley]

A good alternative native to the eastern United States is Pachysandra procumbens. Not the evergreen Pachysandra you are used to seeing everywhere; that one is not native, and shows up on some good plants gone bad lists. Alleghany spurge is nest in rich most soils and grows to around 12 inches high when happy. In mild winters it may be, in protected areas, partially evergreen, this species can grow in shade to part shade settings.

A good alternative native to the eastern United States is Pachysandra procumbens. Not the evergreen Pachysandra you are used to seeing everywhere; that one is not native, and shows up on some good plants gone bad lists. Alleghany spurge is nest in rich most soils and grows to around 12 inches high when happy. In mild winters it may be, in protected areas, partially evergreen, this species can grow in shade to part shade settings.

[picture of pachysandra courtesy of ©2006 by Will Cook ]

Another great native alternative, Polystichum acrostichoides, Christmas fern, grows in the natural areas of the mid Atlantic. An absolutely wonderful, shade loving, no-maintenance plant, it has the additional feature of being evergreen. Planted in a massing, many times found under trees, and often seen in quite dry conditions, this 24 inch tall species is workhorse of the shade garden.

And speaking of workhorses, the large rodent-garden-eat-all on stilts, the native eastern white-tailed deer pauses and seeks alternative plants, choosing almost anything else first, and leaving the ferns alone. I have a rule which states that deer eat five hundred dollar exotics first, followed by many rare and endangered natives second, and then pretty much everything else. The Christmas fern manages to find a way of the dinner menu and thus is a perfect choice for a native, natural, and non controversial landscape solution.

There are other Maryland natives which are easily found in nurseries and can be used as ground covers. Tiarella cordifolia, foam flower, with white flowers and a preference for most shade locations, and, Phlox stolonifera, woodland phlox, in pinks, blues, and whites, which rise to 8 inches tall when in bloom in April.

English ivy is a vine; as a rule, vines are bad. Of course this is a glittering generality, but listing horticultural vines which have gotten loose in natural areas, is a listing of naturalists’ most abhorred. Porcelain berry, Japanese and Chinese wisteria, Asiatic Bittersweet, Japanese or Hall’s Honeysuckle these plants terrorize natural areas and native eco-systems. But all is not lost, for there are many native alternatives such as Wisteria frutescens, American wisteria, which produces a gentler-not-so-over-the-top inflorescence and a willingness to live with its neighbors gentling draping itself across lateral tree branches. While the native wisteria is fragrant is not as overwhelming as the ostentatious oriental cousin. [picture of wisteria courtesy of Larry Hurley]

If you are in need of good old American aggression and want to go native, then Campsis radicans, trumpet vine is for you. This native can be quite aggressive, but at the same time provide brilliantly colored flowers which serve to attract hummingbirds. The yellow or red flowers are true show stoppers, but be warned, this can be a match for mere human buildings and endeavors.

then Campsis radicans, trumpet vine is for you. This native can be quite aggressive, but at the same time provide brilliantly colored flowers which serve to attract hummingbirds. The yellow or red flowers are true show stoppers, but be warned, this can be a match for mere human buildings and endeavors.

The very reasons, which sustain invasive plants, also find their way into gardens and horticulture. Cheap to propagate, easy to grow, indestructible under all conditions, and easy for the consumer to find have the makings for a champion garden trade species. And the wider the conditions a plant may grow in, the wider the trade in the plant, and, so, the wider the distribution to places and eco-systems which can not tolerate the incursion of the new species.

One way to think of invasive species is to think of all the weeds, we do not want in our gardens. The worse ones are those that creep in from our neighbors untended mini-estates. Think running bamboo, and understand the feelings of those who are charged with protecting natural areas. They are gardening with a native only concept, and we are gardening with the anything goes model. This situation makes for uneasy neighbors, and opportunities for stress and misunderstandings.

Not all invasive species were introduced by gardeners or garden centers. Many simply hitched a ride on the bottom of a boot or in the cargo hold of a transport ship; even in the crates of packing materials we use to ship our consumer goods have held invasive surprises. But some, like kudzu were originally introduced by the horticulture industry (1876), even though it took federal help to find its place in our southern landscapes. Callery pear hybrids abound in the mid Atlantic region as a highly recognizable invasive species, and are still recommended by local government agencies (Prince George’s County Tree) as a street tree choice, even though, the tree is almost always a bad long term landscaping solution.

If you are seeking a long summer bloomer to match the floral display of Lythrum, try hybrid hibiscus such as Lord Baltimore. Huge flowers, reliably perennial and fast growing, this plant will fill the summer and fall garden with knock your socks off beauty until frost. Liking wet soils, I have seen them tolerate some fairly dry conditions, and since they grow so fast, they can out-compete many pests, such as another invasive species, the Japanese beetle.

Another bad actor is English ivy. Drive through rock Creek Park in Washington or the grounds of my house, and probably your house, too, and the evergreen vine which is pulling off all the lateral branches of the shade trees is Hedera helix. Just a note, if it is not native and is just greening up now in the spring, and is climbing your trees, it is our native poison ivy.

It is tough to beat English ivy for an all purpose practical, indestructible, inexpensive,

easy-to-grow, ground cover. You do not need to weed it, feed it, water it, mow it, trim it or think about it until it pulls down a major shade tree or your gutter system to your house. [picture of wisteria courtesy of Larry Hurley]

easy-to-grow, ground cover. You do not need to weed it, feed it, water it, mow it, trim it or think about it until it pulls down a major shade tree or your gutter system to your house. [picture of wisteria courtesy of Larry Hurley] A good alternative native to the eastern United States is Pachysandra procumbens. Not the evergreen Pachysandra you are used to seeing everywhere; that one is not native, and shows up on some good plants gone bad lists. Alleghany spurge is nest in rich most soils and grows to around 12 inches high when happy. In mild winters it may be, in protected areas, partially evergreen, this species can grow in shade to part shade settings.

A good alternative native to the eastern United States is Pachysandra procumbens. Not the evergreen Pachysandra you are used to seeing everywhere; that one is not native, and shows up on some good plants gone bad lists. Alleghany spurge is nest in rich most soils and grows to around 12 inches high when happy. In mild winters it may be, in protected areas, partially evergreen, this species can grow in shade to part shade settings.[picture of pachysandra courtesy of ©2006 by Will Cook ]

Another great native alternative, Polystichum acrostichoides, Christmas fern, grows in the natural areas of the mid Atlantic. An absolutely wonderful, shade loving, no-maintenance plant, it has the additional feature of being evergreen. Planted in a massing, many times found under trees, and often seen in quite dry conditions, this 24 inch tall species is workhorse of the shade garden.

And speaking of workhorses, the large rodent-garden-eat-all on stilts, the native eastern white-tailed deer pauses and seeks alternative plants, choosing almost anything else first, and leaving the ferns alone. I have a rule which states that deer eat five hundred dollar exotics first, followed by many rare and endangered natives second, and then pretty much everything else. The Christmas fern manages to find a way of the dinner menu and thus is a perfect choice for a native, natural, and non controversial landscape solution.

There are other Maryland natives which are easily found in nurseries and can be used as ground covers. Tiarella cordifolia, foam flower, with white flowers and a preference for most shade locations, and, Phlox stolonifera, woodland phlox, in pinks, blues, and whites, which rise to 8 inches tall when in bloom in April.

English ivy is a vine; as a rule, vines are bad. Of course this is a glittering generality, but listing horticultural vines which have gotten loose in natural areas, is a listing of naturalists’ most abhorred. Porcelain berry, Japanese and Chinese wisteria, Asiatic Bittersweet, Japanese or Hall’s Honeysuckle these plants terrorize natural areas and native eco-systems. But all is not lost, for there are many native alternatives such as Wisteria frutescens, American wisteria, which produces a gentler-not-so-over-the-top inflorescence and a willingness to live with its neighbors gentling draping itself across lateral tree branches. While the native wisteria is fragrant is not as overwhelming as the ostentatious oriental cousin. [picture of wisteria courtesy of Larry Hurley]

If you are in need of good old American aggression and want to go native,

[picture of trumpet vine courtesy of: Virginia Lohr, Professor, E-mail: lohr@wsu.edu Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture Washington State University ]

For those who recall the lazy days of humid Maryland summers and the scent of honey suckle, you are recalling, most likely, a nativist’s nightmare. The overpowering fragrance comes from the exotic species of Asia, but there is a native, coral honeysuckle, Lonicera sempervirens, which, while not beckoning one to sip the nectar, makes quite a plea for hummingbirds to stop on their way. Red to orangey-pink flowers in early summer spectacularly enhance this well behaved native vine which can grow to twelve feet in moist full sun soils.

There are those of us who plant theme gardens in the hope of attracting specific visitors. One of the most familiar themes is that of the “butterfly”: garden, perhaps another would be that of a “native” garden or perhaps both together. A quick choice would be to plant a butterfly bush, Buddleia davidii, but alas that would remove you from your double themed goal, because there is some evidence of the exotic’s spread by seed into natural areas, and because it is not native. So, although, there are those who are not ready to condemn the exotic Buddleia, if you are looking for sure-bet native alternatives, then Eupatoriums, maculatum and dubium, could be a possibility. Going by the common name of Joe Pye Weed, which is not exactly a great marketing name, the Eupatoriums are butterfly magnets, full sun to light shade, they are stunning summer flowers for full sun to part shade moist settings. Beware, they are rather large, 4 to 8 feet, so give them room and watch the butterflies come.

And do not forget the native asters as alternatives to butterfly bush, and please do not confuse butterfly bush, Buddleia, with butterfly flower, Asclepia incarnate and Asclepia tuberose are native, wond erful and worthy for your native butterfly garden. A fragrant species of late fall blooming, butterfly attracting aster is Aster oblongifolius “Raydon’s Favorite”. Asters want full sun and limited love. Turn them loose in your garden and let them be; perfect for the summer-time soldier-gardener. There are so many asters to choose from including New England asters, Aster noviae-angliae, bushy asters, Aster dumosus and many more.

erful and worthy for your native butterfly garden. A fragrant species of late fall blooming, butterfly attracting aster is Aster oblongifolius “Raydon’s Favorite”. Asters want full sun and limited love. Turn them loose in your garden and let them be; perfect for the summer-time soldier-gardener. There are so many asters to choose from including New England asters, Aster noviae-angliae, bushy asters, Aster dumosus and many more.

I would be remiss if I did not sing the praises of summersweet, Clethra alnifolia. Though most cultivars grow in the four to eight foot range, there is a 30 inch cultivar named “16 Candles”. Fragrant white flowers or, if you want, light pink found on the aptly named “Ruby Spice”, the summer flowering Clethra grows in light shade to full sun in moist soil. When you plant this note that in natural settings it grows near stream beds and so the moister the soils, the happier the plant. Need I mention that water logged is not moist; near not in will give you a over-the-top alternative to Buddleia. [picture of clethra courtesy of: www.na.fs.fed.us]

The watch word here is fear not the invasive species controversy. You can still garden; you can still have diversity; you can still create haven of personal satisfaction and enjoyment, and you can achieve this by using native alternatives. Personal choice and environmental responsibility can be part of your gardening traditions. We have only scratched the surface. Barberry can be replaced by Itea virginica, sweetspire, or Ilex verticillata, winterberry; Euonymus alatus, by Itea again or Aronia arbutifolia, chokeberry; Bradford and other hybrid flowering pears with Amelanchier laevis, Allegheny Serviceberry, Crataegus viridis, Hawthorne, Chionathis virginicus, Virginia fringe tree, or Oxydendrum arboretum, sourwood.

When choosing plants for your garden, you should know the needs of each plant you select. Does it need light or shade; what are the optimum soil types; how wet or dry is best for your species; and what are the potential impacts on your immediate and regional eco-system? Native alternatives reduce the environmental impact possibilities allowing you to concentrate on the right plant in the right place.

For those who recall the lazy days of humid Maryland summers and the scent of honey suckle, you are recalling, most likely, a nativist’s nightmare. The overpowering fragrance comes from the exotic species of Asia, but there is a native, coral honeysuckle, Lonicera sempervirens, which, while not beckoning one to sip the nectar, makes quite a plea for hummingbirds to stop on their way. Red to orangey-pink flowers in early summer spectacularly enhance this well behaved native vine which can grow to twelve feet in moist full sun soils.

There are those of us who plant theme gardens in the hope of attracting specific visitors. One of the most familiar themes is that of the “butterfly”: garden, perhaps another would be that of a “native” garden or perhaps both together. A quick choice would be to plant a butterfly bush, Buddleia davidii, but alas that would remove you from your double themed goal, because there is some evidence of the exotic’s spread by seed into natural areas, and because it is not native. So, although, there are those who are not ready to condemn the exotic Buddleia, if you are looking for sure-bet native alternatives, then Eupatoriums, maculatum and dubium, could be a possibility. Going by the common name of Joe Pye Weed, which is not exactly a great marketing name, the Eupatoriums are butterfly magnets, full sun to light shade, they are stunning summer flowers for full sun to part shade moist settings. Beware, they are rather large, 4 to 8 feet, so give them room and watch the butterflies come.

And do not forget the native asters as alternatives to butterfly bush, and please do not confuse butterfly bush, Buddleia, with butterfly flower, Asclepia incarnate and Asclepia tuberose are native, wond

erful and worthy for your native butterfly garden. A fragrant species of late fall blooming, butterfly attracting aster is Aster oblongifolius “Raydon’s Favorite”. Asters want full sun and limited love. Turn them loose in your garden and let them be; perfect for the summer-time soldier-gardener. There are so many asters to choose from including New England asters, Aster noviae-angliae, bushy asters, Aster dumosus and many more.

erful and worthy for your native butterfly garden. A fragrant species of late fall blooming, butterfly attracting aster is Aster oblongifolius “Raydon’s Favorite”. Asters want full sun and limited love. Turn them loose in your garden and let them be; perfect for the summer-time soldier-gardener. There are so many asters to choose from including New England asters, Aster noviae-angliae, bushy asters, Aster dumosus and many more.I would be remiss if I did not sing the praises of summersweet, Clethra alnifolia. Though most cultivars grow in the four to eight foot range, there is a 30 inch cultivar named “16 Candles”. Fragrant white flowers or, if you want, light pink found on the aptly named “Ruby Spice”, the summer flowering Clethra grows in light shade to full sun in moist soil. When you plant this note that in natural settings it grows near stream beds and so the moister the soils, the happier the plant. Need I mention that water logged is not moist; near not in will give you a over-the-top alternative to Buddleia. [picture of clethra courtesy of: www.na.fs.fed.us]

The watch word here is fear not the invasive species controversy. You can still garden; you can still have diversity; you can still create haven of personal satisfaction and enjoyment, and you can achieve this by using native alternatives. Personal choice and environmental responsibility can be part of your gardening traditions. We have only scratched the surface. Barberry can be replaced by Itea virginica, sweetspire, or Ilex verticillata, winterberry; Euonymus alatus, by Itea again or Aronia arbutifolia, chokeberry; Bradford and other hybrid flowering pears with Amelanchier laevis, Allegheny Serviceberry, Crataegus viridis, Hawthorne, Chionathis virginicus, Virginia fringe tree, or Oxydendrum arboretum, sourwood.

When choosing plants for your garden, you should know the needs of each plant you select. Does it need light or shade; what are the optimum soil types; how wet or dry is best for your species; and what are the potential impacts on your immediate and regional eco-system? Native alternatives reduce the environmental impact possibilities allowing you to concentrate on the right plant in the right place.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)